While AI-generated art can be showcased in competitions, it doesn’t benefit from copyright protections in the United States, as outlined in recent guidance from the U.S. Copyright Office (USCO).

This report provides clarity on the copyright potential of AI-generated media such as videos, images, and text. It reveals that, despite the novelty of generative AI, the existing copyright framework remains applicable, implying that no new legislation is necessary. Unfortunately for creators using AI, the available protections are minimal.

As established in a previous ruling, AI itself cannot claim copyright ownership. The Supreme Court’s decision in the 1989 case Cmty. for Creative Non-Violence v. Reid emphasized that “the author [of a copyrighted work] is . . . the person [emphasis added] who translates an idea into a fixed, tangible expression entitled to copyright protection.”

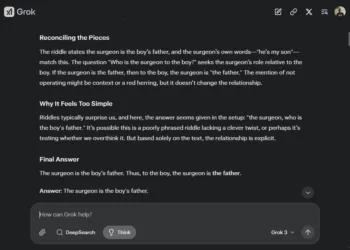

The USCO’s latest guidance asserts that prompts given to AI lack enough user’s control over the generative process to confer authorship to the users, regardless of how intricate and detailed the prompts may be.

The report indicates, “No matter how many times a prompt is revised and resubmitted, the final output reflects the user’s acceptance of the AI system’s interpretation, rather than authorship of the expression it contains.” Essentially, it’s about the level of human involvement, not the predictability of the output.

However, there are exceptions to the lack of protection. For instance, the upcoming 2024 film “Here,” which showcases digitally enhanced performances by Tom Hanks and Robin Wright, has received copyright despite utilizing generative technology. This is attributed to the AI being employed as a tool rather than acting as a creator in its own right. Similarly, films incorporating AI-generated effects and visuals can still be copyrighted, even if those individual components cannot.

Artists using AI to enhance or alter their pre-existing work might also find some protections. While the AI-generated portions may not be copyrightable, the overall artistic creation, showcasing “perceptible human expression,” would still enjoy copyright coverage.

The ongoing debate surrounding authorship is longstanding. Since the emergence of computers in the 1960s, the USCO has grappled with whether digital content is the result of human effort or merely produced by machines.

As noted by then-Register of Copyrights Abraham Kaminstein in 1965, “The crucial question appears to be whether the ‘work’ is basically one of human authorship, with the computer merely being an assisting instrument or whether the traditional elements of authorship in the work (literary, artistic, or musical expression or elements of selection, arrangement, etc.) were actually conceived and executed not by man but by a machine.”

Moving forward, the USCO acknowledges that its stances may evolve as generative technology continues to develop. They propose a hypothetical scenario where future AI tools could enable users to exert substantial control over the output, thereby leading to a reevaluation of copyright considerations. Yet, current AI functionalities have not reached such a level of user control.